In Nature today, Dan Sarewitz offers up a New Year's resolution for scientists:

To prevent science from continuing its worrying slide towards politicization, here’s a New Year’s resolution for scientists, especially in the United States: gain the confidence of people and politicians across the political spectrum by demonstrating that science is bipartisan.That a call for science to demonstrate that it is not a partisan endeavor is necessary is reflective of the degree to which leading scientific institutions in the United States (and elsewhere as well) have become deeply partisan bodies. Sarewitz explains:

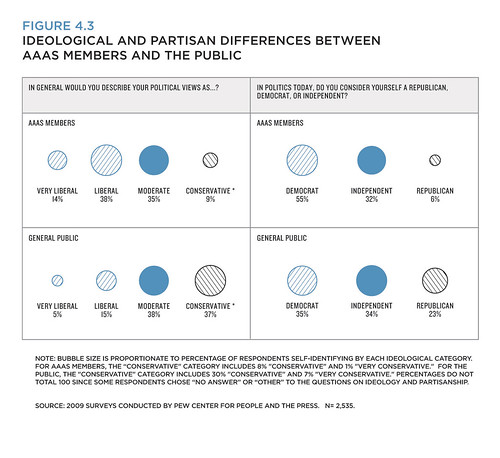

[S]cience has come, over the past decade or so, to be a part of the identity of one political party, the Democrats, in the United States. The highest-profile voices in the scientific community have avidly pursued this embrace. For the third presidential election in a row, dozens of Nobel prizewinners in physics, chemistry and medicine signed a letter endorsing the Democratic candidate.Partisanship within the scientific community shows itself not just in elections but in how the science community positions itself with respect to government. For a while now several scientific associations (especially AAAS and AGU) have taken on the role of seeing Democrats as allies and Republicans as opponents.

The 2012 letter argued that Obama would ensure progress on the economy, health and the environment by continuing “America’s proud legacy of discovery and invention”, and that his Republican opponent, Mitt Romney, would “devastate a long tradition of support for public research and investment in science”. The signatories wrote “as winners of the Nobel Prizes in Science”, thus cleansing their endorsement of the taint of partisanship by invoking their authority as pre-eminent scientists.

But even Nobel prizewinners are citizens with political preferences. Of the 43 (out of 68) signatories on record as having made past political donations, only five had ever contributed to a Republican candidate, and none did so in the last election cycle. If the laureates are speaking on behalf of science, then science is revealing itself, like the unions, the civil service, environmentalists and tort lawyers, to be a Democratic interest, not a democratic one.

John Besley and Matt Nisbet documented this phenomenon in a recent paper and explain how the nature of social media serves to amplify partisanship:

With an ever-increasing reliance on blogs, Facebook and personalized news, the tendency among scientists to consume, discuss and refer to self-confirming information sources is only likely to intensify, as will in turn the criticism directed at those who dissent from conventional views on policy or public engagement strategy. Moreover, if perceptions of bias and political identity do indeed strongly influence the participation of scientists in communication outreach via blogs, the media or public forums, there is the likelihood that the most visible scientists across these contexts are also likely to be among the most partisan and ideological.Such dynamics are found in more conventional media as well. In a 2009 paper I documented that Science magazine published 40 editorials critical of the Bush Administration during its 2 terms, and only 1 such critique of the Clinton Administration's previous 2 terms (here in PDF). I have just updated this analysis through the first term of the Obama Administration, and found no editorials critical of the Obama Administration. Instead, there were editorials with the following titles:

An approach that critiques the president when he is a Republican and cheer-leads when he is a Democrat lends itself to more than just cynicism -- it contributes to the politicization of science policy issues which by their nature can be problematic regardless of who is in office.

I have often marveled on this blog at how issues of scientific integrity -- which were so important to scientists and science connoisseurs during the Bush Administration -- largely disappeared in social media science policy discussions, and only occasionally appeared in the conventional media.

The issues, however, have not disappeared. A few weeks ago, the Union of Concerned Scientists observed in the case of genetically modified salmon:

Despite what the President might have said about scientific integrity, we’ve seen White House interference on what should be science regulatory decisions.A list of troubling issues under the Obama Administration where science and politics meet is, well, almost Bush-like, and includes issues related to drilling safety, the muzzling of scientists at USDA and at HHS, clothing political decisions in dodgy scientific claims on the morning after pill and Yucca Mountain, the withholding of scientific information for fear of political fallout ... and the list goes on.

For those who care about scientific integrity, the selective attention of the scientific community is problematic because it reduces the issue to a matter of electoral politics rather than the nitty-gritty details of actual policy implementation.

Sarewitz finds another reason to object:

This is dangerous for science and for the nation. The claim that Republicans are anti-science is a staple of Democratic political rhetoric, but bipartisan support among politicians for national investment in science, especially basic research, is still strong. For more than 40 years, US government science spending has commanded a remarkably stable 10% of the annual expenditure for non-defence discretionary programmes. In good economic times, science budgets have gone up; in bad times, they have gone down. There have been more good times than bad, and science has prospered.For partisans, none of this analysis makes sense because their goal is to simply vanquish their political opponents. That science has become aligned with the Democratic party is, from where they sit, not a problem but a positive. Thus more partisanship is needed, not less. I have no illusions of convincing the extreme partisans of the merit in Sarewitz's view. I do think that there are many in the scientific community who object to the exploitation of scientific institutions to the detriment of both science and decision making, and no doubt it is to this group that Sarewitz's resolution is offered.

In the current period of dire fiscal stress, one way to undermine this stable funding and bipartisan support would be to convince Republicans, who control the House of Representatives, that science is a Democratic special interest.

This concern rests on clear precedent. Conservatives in the US government have long been hostile to social science, which they believe tilts towards liberal political agendas. Consequently, the social sciences have remained poorly funded and politically vulnerable, and every so often Republicans threaten to eliminate the entire National Science Foundation budget for social science.

There are promising signs that the partisan wave which has engulfed the scientific community over the past decade is receding somewhat. This is good news. But the scientific community still has a lot of work to do. Sarewitz offers some helpful advice:

The US scientific community must decide if it wants to be a Democratic interest group or if it wants to reassert its value as an independent national asset. If scientists want to claim that their recommendations are independent of their political beliefs, they ought to be able to show that those recommendations have the support of scientists with conflicting beliefs. Expert panels advising the government on politically divisive issues could strengthen their authority by demonstrating political diversity. The National Academies, as well as many government agencies, already try to balance representation from the academic, non-governmental and private sectors on many science advisory panels; it would be only a small step to be equally explicit about ideological or political diversity. Such information could be given voluntarily.There is of course nothing wrong with partisanship or with scientists participating in politics, they are after all citizens. However, our scientific institutions are far too important to be allowed to become pawns in the political battles of the day.

To connect scientific advice to bipartisanship would benefit political debate. Volatile issues, such as the regulation of environmental and public-health risks, often lead to accusations of ‘junk science’ from opposing sides. Politicians would find it more difficult to attack science endorsed by avowedly bipartisan groups of scientists, and more difficult to justify their policy preferences by scientific claims that were contradicted by bipartisan panels.

During the cold war, scientists from America and the Soviet Union developed lines of communication to improve the prospects for peace. Given the bitter ideological divisions in the United States today, scientists could reach across the political divide once again and set an example for all.